How a simple urine test could save the lives of kidney transplant patients

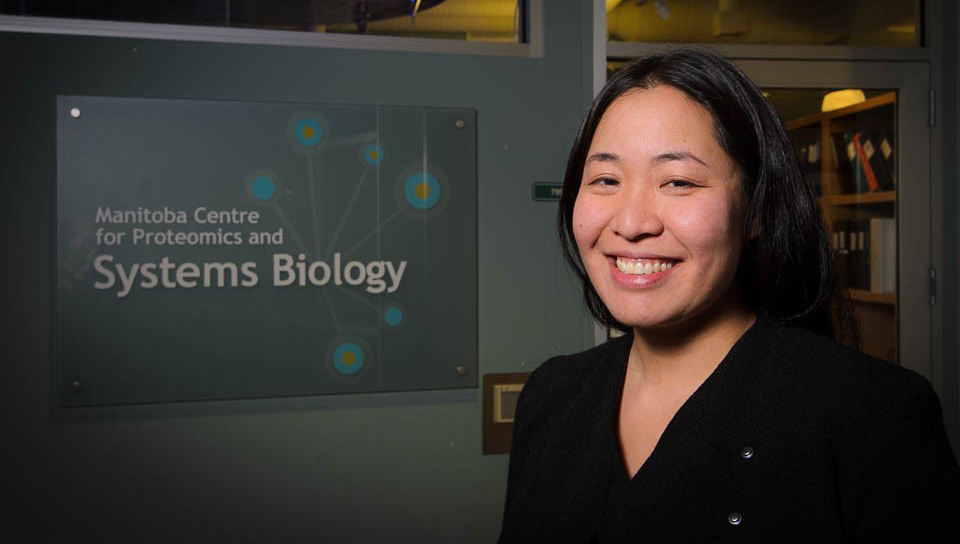

It's the fuel that drives most physicians, including Dr. Julie Ho: a passion to help people.

"I see my patients and get to have these very long relationships with these incredible people," says Dr. Ho, a transplant nephrologist and professor of internal medicine at the University of Manitoba.

As a transplant nephrologist, Dr. Ho cares for and treats patients before and after their kidney transplants. Her treatment plans last years, guiding patients through some of their darkest days to some of their brightest. She is there every step of the way.

"Transplantation is one of the few places in medicine that is usually a very happy place. When people come to the hospital to get their kidney, they want to be there," she says. "It is a privilege to be a part of that journey."

But with all the good that comes from a successful kidney transplant, there are difficult times, too. Dr. Ho says that is especially true when a transplant doesn't go as hoped. On average, 1,700 people receive a kidney transplant every year in Canada, and of those, about one-third will suffer rejection within the first year post-transplant.

"It is really devastating when a patient's body rejects the transplant because it may force them back into kidney failure and back on dialysis," she explains. "Trying to find ways to make their transplant last longer is what really motivates me in my work."

Identifying kidney rejection sooner

The current standard of care for kidney transplant patients involves monitoring for rejection via a routine blood test called "serum creatinine." Serum creatinine is a measure of kidney function, but it doesn't measure kidney injury or inflammation, which makes it difficult for doctors to know whether a patient's body is rejecting the transplant.

"The kidney is a tough organ," Dr. Ho says. "You can do a lot of damage to it before you lose enough function that the serum creatinine marker will actually show up in your blood work and prompt doctors to do a biopsy to look for signs of rejection. Often, by the time it's detected, the kidney has already suffered scarring and it becomes harder to save it."

When this happens and the patient spirals back into kidney failure and dialysis, it comes at a high cost to not only the patient's quality of life and mental health, but also to the health care system. Kidney dialysis can cost up to $100,000 a year per patient, as opposed to a kidney transplant, which averages about $60,000 to perform and up to $24,000 each year after to maintain.

"Of course, it isn't just about the money," explains Dr. Ho, "but when you look at the potential cost savings to the system, it becomes yet another reason to find better ways to make this work."

Inspired by her mentor and colleague Dr. David Rush, who identified that kidney rejection can't be detected on routine blood tests, Dr. Ho has studied a urine test that could help. The test is designed to detect the presence of a specific protein that is released when a patient's body is in the early stages of rejecting their kidney. The test is at the centre of a five-year research study, which has shown that it is possible to see early signs of kidney damage about four weeks sooner than when the traditional serum creatinine marker would normally detect it.

That extra time is crucial for early intervention, Dr. Ho stresses. "Once we see those early signs of rejection, we can take the appropriate measures to treat patients right away," she says. "Our research has shown that if we act as soon as the urine test shows high levels of this protein, and if we treat the patient with anti-rejection medication, the protein levels will go back down again – suggesting patients' bodies may have stopped rejecting the kidney. Essentially, we hope this will lengthen the time the patient's kidney transplant will last."

Dr. Ho and her team are in the midst of a large collaborative clinical trial with ten health centres in Canada and Australia to measure the effectiveness of the urine test. The team believes it could one day become a new standard of care. Currently, the test is analyzed in a lab, but the team hopes to develop the technology to make it a simple rapid test – similar to a home pregnancy test – that could be used widely around the world.

"This would be huge for rural and remote communities across Canada, including Indigenous communities," explains Dr. Ho. "If these tests are something that could be easily administered in rural hospitals and clinics with limited resources, or even if they could be used by a patient in their home, then it may greatly improve the lives of transplant patients across the country."

Building on research to help improve patient care

Dr. Ho is now exploring whether a similar urine test could be developed to identify – within the first year after transplant – which patients are at higher risk of losing their kidney.

"This is a more proactive approach to identify people who are at a higher risk of losing their kidney transplant because of rejection or because their original kidney disease is coming back," says Dr. Ho. "We are using a similar urine test to check proteins in the urine to identify people who are at high risk. If we can identify them, then doctors could monitor these patients more closely, treat them more aggressively, or tailor their care to make sure the patient keeps their kidney transplant for as long as possible."

This latest study is at the observational stage and Dr. Ho plans to move it to the clinical trial stage within the next few years. She is grateful for the investment in her research, an investment she says will improve care for not only Canadians but people around the world.

"The field of science and medicine is made up of building blocks," says Dr. Ho. "We continue to build on the discoveries and innovations of the people who have done work before us. I hope that the work we're doing now extends the length of time kidney transplants last and will ultimately extend the lives of kidney transplant patients."

- Date modified: